What does the melting of the Arctic really mean ?

For humanity and for us as campaigners.

Well, in a nutshell, I think it means that none of the measures we are taking, or, even in the more optimistic political

scenarios, are likely to take, will stop us colliding head on with the catastrophic impacts of climate change.

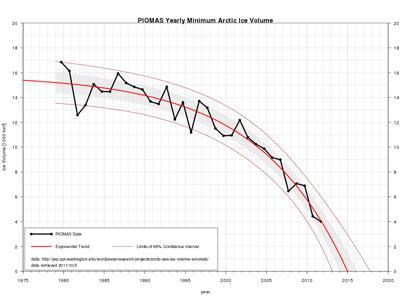

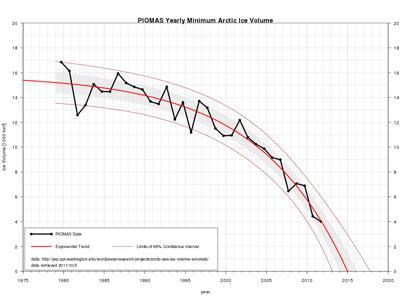

What happened to the Arctic last year ? Well at its lowest summer extent the sea ice cover shrunk back around 700,000 sq

km more than it ever has before - to an area roughly half the average from 1979 to 2000. Meanwhile the situation as to the

volume of ice is a little more controversial due to the greater difficulty of measurement but it is certainly a lot more

dramatic with maybe 70 to 80 % disappeared, and diminishing on a trajectory, which, according to Professor Peter Wadhams

from the Cambridge University Polar Ocean Physics Group will bring us to essentially zero end of summer sea ice by 2015

(see

further here and here ).

What happened to the Arctic last year ? Well at its lowest summer extent the sea ice cover shrunk back around 700,000 sq

km more than it ever has before - to an area roughly half the average from 1979 to 2000. Meanwhile the situation as to the

volume of ice is a little more controversial due to the greater difficulty of measurement but it is certainly a lot more

dramatic with maybe 70 to 80 % disappeared, and diminishing on a trajectory, which, according to Professor Peter Wadhams

from the Cambridge University Polar Ocean Physics Group will bring us to essentially zero end of summer sea ice by 2015

(see

further here and here ).

Given that Professor Wadham's credibility has received a huge boost from the dramatically precipitate crash in sea ice last

year we would be very unwise to dismiss his prediction, based as he says on a measured trend. What that means is that

what was - a decade or so ago - routinely predicted not to happen till the end of the century, or maybe 80 years hence, is

happening, essentially, right now. There could hardly be a more dramatic, nor a more clear cut, demonstration of the fact

that climate change is happening far quicker than anyone predicted and that the predictions of the scientists are falling

way short of the reality: even the scientists have been left floundering in the wake of the climate change behomoth, forever

struggling to revise upwards their estimates of its scale and speed. With a few exceptions this has been overwhelmingly

the case across the board (just compare standard scientific estimates from 10, from 20, years ago in so many fields) but

the precipitate decline of arctic sea ice is the clearest and most dramatic.

Given that Professor Wadham's credibility has received a huge boost from the dramatically precipitate crash in sea ice last

year we would be very unwise to dismiss his prediction, based as he says on a measured trend. What that means is that

what was - a decade or so ago - routinely predicted not to happen till the end of the century, or maybe 80 years hence, is

happening, essentially, right now. There could hardly be a more dramatic, nor a more clear cut, demonstration of the fact

that climate change is happening far quicker than anyone predicted and that the predictions of the scientists are falling

way short of the reality: even the scientists have been left floundering in the wake of the climate change behomoth, forever

struggling to revise upwards their estimates of its scale and speed. With a few exceptions this has been overwhelmingly

the case across the board (just compare standard scientific estimates from 10, from 20, years ago in so many fields) but

the precipitate decline of arctic sea ice is the clearest and most dramatic.

And so what's

going on in the Arctic ? Or more to the point what looks now likely to happen in the Arctic ? And how will

it effect us ? The answer in brief is that a whole range of feedback mechanisms have been triggered and are queuing up to

spring powerfully into force.  One should note that the Arctic has been warming disproportionately faster than the rest of

the planet (in part because of feedbacks already in operation) and that is part of the reason for why we are where we are

but the relevant feedbacks now set to dramatically accelerate the warming process include diminished albedo (that is

reflection away of the sun's heat) from diminished sea ice and seasonal snow cover on land (with dark ocean or land surfaces

absorbing more heat), release of carbon, mainly in the form of methane, from melting permafrost on land and release of

yet more methane from the methane hydrates under the sea. Professor Wadhams

has calculated that loss of albedo already

accounts for as much warming as about 20 years of human emissions:

I am told that this estimate is considerably off the

mark when compared with other (smaller) ones and we should seize every opportunity we have not to believe Professor Wadhams

and his gloomy prognoses. Nevertheless loss of albedo is still a very considerable feedback effect.

One should note that the Arctic has been warming disproportionately faster than the rest of

the planet (in part because of feedbacks already in operation) and that is part of the reason for why we are where we are

but the relevant feedbacks now set to dramatically accelerate the warming process include diminished albedo (that is

reflection away of the sun's heat) from diminished sea ice and seasonal snow cover on land (with dark ocean or land surfaces

absorbing more heat), release of carbon, mainly in the form of methane, from melting permafrost on land and release of

yet more methane from the methane hydrates under the sea. Professor Wadhams

has calculated that loss of albedo already

accounts for as much warming as about 20 years of human emissions:

I am told that this estimate is considerably off the

mark when compared with other (smaller) ones and we should seize every opportunity we have not to believe Professor Wadhams

and his gloomy prognoses. Nevertheless loss of albedo is still a very considerable feedback effect.

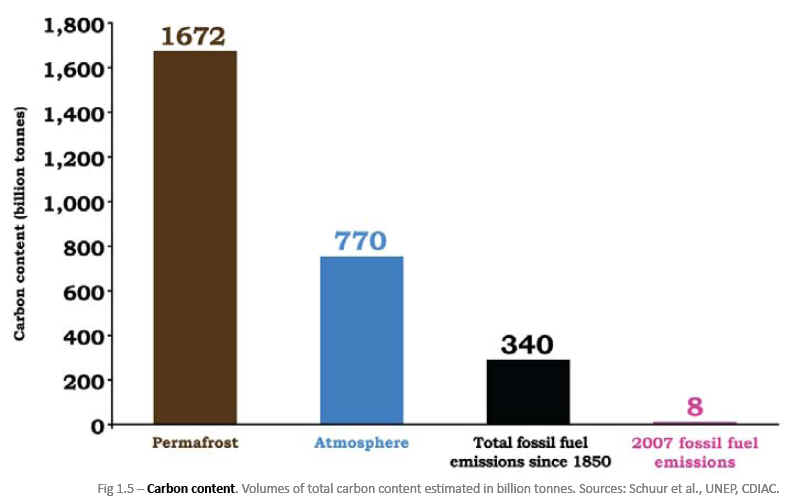

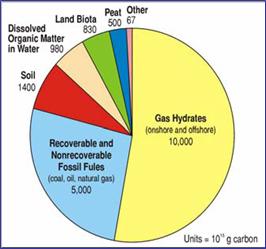

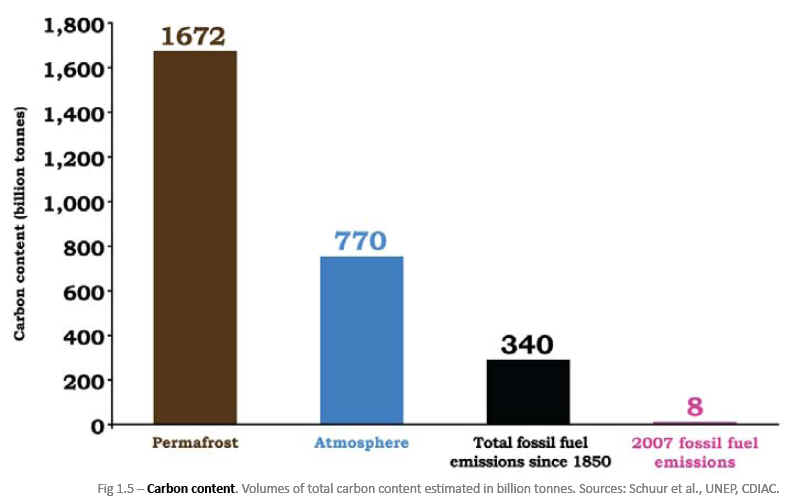

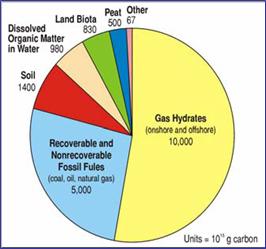

There is, meanwhile,

maybe twice as much carbon in the permafrost than currently in the atmosphere whilst an even greater quantity resides in

the methane hydrates, massive releases from which have been implicated as the dominant mechanism behind several of the

extinction events from the distant geological past, in particular the

End-Permian, the most dramatic of all, said to

have wiped out 95% of life at the time. However what matters to us is just how fast the process of CO2 and methane release

from these sources proceeds, or its rate of acceleration, in the near future on a human time scale. Meanwhile I have not

mentioned a long list of more esoteric feedbacks which include for instance increased waviness in a sea with less ice cover

accelerating the break-up and melting of sea ice, black soot from increased tundra fires settling on snow and ice and

further diminishing albedo and speeding melting and I am sure quite a few others I am simply not up to speed on (see a

discussion on the gravity of the 'arctic crisis

here ).

The point about all of these is that, whilst we know little about precisely how fast they will spring into life we do know that,

pretty much without exception, they are not taken into account in standard estimates of how fast the climate will warm, how

much more carbon we can burn and how fast we have to act.

There is, meanwhile,

maybe twice as much carbon in the permafrost than currently in the atmosphere whilst an even greater quantity resides in

the methane hydrates, massive releases from which have been implicated as the dominant mechanism behind several of the

extinction events from the distant geological past, in particular the

End-Permian, the most dramatic of all, said to

have wiped out 95% of life at the time. However what matters to us is just how fast the process of CO2 and methane release

from these sources proceeds, or its rate of acceleration, in the near future on a human time scale. Meanwhile I have not

mentioned a long list of more esoteric feedbacks which include for instance increased waviness in a sea with less ice cover

accelerating the break-up and melting of sea ice, black soot from increased tundra fires settling on snow and ice and

further diminishing albedo and speeding melting and I am sure quite a few others I am simply not up to speed on (see a

discussion on the gravity of the 'arctic crisis

here ).

The point about all of these is that, whilst we know little about precisely how fast they will spring into life we do know that,

pretty much without exception, they are not taken into account in standard estimates of how fast the climate will warm, how

much more carbon we can burn and how fast we have to act.

Before tackling the likely longer term implications of that we can take a look at how this is actually affecting us,

already, right now. Recent studies have increasingly suggested that not only are extreme weather events increasing in line

with increased global temperature and energy in the system (demonstrated statistically in a recent Hansen study) but the

disproportionately rapid warming of the Arctic itself is causing abnormal jet stream behaviour that has been implicated in

a large number of recent extreme weather events (see my previous blog

here). It looks like disproportionate Arctic warming and the rapid changes taking

place there are becoming the dominant driver of extreme weather, certainly in the Northern Hemisphere. This extreme weather

meanwhile has been impacting agriculture, destroying crops and forcing up food prices. Given the precariousness of our

current global food system it isn't hard to see how the likely acceleration of the Arctic meltdown will precipitate a

perfect storm of rising food prices, food shortages, social unrest and conflict. Its true there is plenty of

disfunctionality anyway in the food system (as many in assorted NGOs will tell you) and so you could say plenty of potential

slack in terms of room for improvements we could make - but there is no guarantee these improvements will be made and

anyway the prospect that even these could be ultimately overwhelmed by the magnitude of the climate change impacts.

Before tackling the likely longer term implications of that we can take a look at how this is actually affecting us,

already, right now. Recent studies have increasingly suggested that not only are extreme weather events increasing in line

with increased global temperature and energy in the system (demonstrated statistically in a recent Hansen study) but the

disproportionately rapid warming of the Arctic itself is causing abnormal jet stream behaviour that has been implicated in

a large number of recent extreme weather events (see my previous blog

here). It looks like disproportionate Arctic warming and the rapid changes taking

place there are becoming the dominant driver of extreme weather, certainly in the Northern Hemisphere. This extreme weather

meanwhile has been impacting agriculture, destroying crops and forcing up food prices. Given the precariousness of our

current global food system it isn't hard to see how the likely acceleration of the Arctic meltdown will precipitate a

perfect storm of rising food prices, food shortages, social unrest and conflict. Its true there is plenty of

disfunctionality anyway in the food system (as many in assorted NGOs will tell you) and so you could say plenty of potential

slack in terms of room for improvements we could make - but there is no guarantee these improvements will be made and

anyway the prospect that even these could be ultimately overwhelmed by the magnitude of the climate change impacts.

But lets get back to the feedbacks. And the rapidly evolving physical reality that seems to be leaving the scientists

behind. It is hard not to feel that what is happening in the Arctic represents a tipping point. Well what exactly is a

tipping point ? Its a discontinuity, a non-linearity (you cant beat the euphemisms of doom !), something which, when

you've made a graph of it in the future, exhibits a sudden sharp bend, or change in direction. It doesn't necessarily mean

the sky will fall in tomorrow. And what might appear as a clear sharp kink, a change of direction that happened almost in

an instant, from the perspective of geological time, might appear very differently as it happens, on a human time scale.

But what it does mean is that all the calculations and predictions that were based on that steadily curving graph, that

predicted curve, now go out the window. Something else has taken over that has its own - possibly quite chaotic - logic. I

asked Peter Wadhams when we were privileged to have a lecture given by him, why it was that many other scientists disagreed

(or had disagreed) with many of his conclusions. His answer, as I understood it, was that some scientists based their

conclusions on models whilst

others, amongst whom he included himself, based theirs on the data. That spoke volumes to me: of course models are

based

ultimately on data but from a multitude of sources to get an overall picture as in the one captured by that curving line

on the graph. Meanwhile hard data - carefully collected and rigorously analysed - from just one single source might discredit

the whole thing. Or at least that is the kind of thing that happens when you hit a 'tipping point': some factor or factors

not included, or inadequately assessed, in the model, has or have taken over and its time to throw the model out of the

window - and with it any illusions you have about the predictability of the future. That piece of hard data may now be

a better clue to the future and its best to look very hard at that, though without any illusion that it will give you any

kind of complete picture.

Now when I said its hard not to feel (that we're witnessing a 'tipping point') it may not have been lost on some readers

that feeling something hardly constitutes a rigorous scientific proof. and of course I am neither a scientist nor capable

of providing any kind of measured scientific analysis to prove the point. There might be some elements of the science there

is not the space to go into here which I might have used to paint a picture that would better support my contention. Like

the scale of the anthropogenic impact on a sensitive system, or the evidence that we have already put a quantity of

greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that on the basis of the way the planet has behaved in the past means that (unless we

can take some out of the atmosphere) we are headed for a scale of temperature rise that can only be catastrophic. But

ultimately I can only say that: looking at what's going on around us and on the basis of what I know about the science this

is what it looks like to me. What does it look like to you ?

Now when I said its hard not to feel (that we're witnessing a 'tipping point') it may not have been lost on some readers

that feeling something hardly constitutes a rigorous scientific proof. and of course I am neither a scientist nor capable

of providing any kind of measured scientific analysis to prove the point. There might be some elements of the science there

is not the space to go into here which I might have used to paint a picture that would better support my contention. Like

the scale of the anthropogenic impact on a sensitive system, or the evidence that we have already put a quantity of

greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that on the basis of the way the planet has behaved in the past means that (unless we

can take some out of the atmosphere) we are headed for a scale of temperature rise that can only be catastrophic. But

ultimately I can only say that: looking at what's going on around us and on the basis of what I know about the science this

is what it looks like to me. What does it look like to you ?

And I would like at this point to have a little poke at the scientists (or some of them). Don't get me wrong I am deeply

grateful for what they do and some like Hansen and Mann have been heroic under the unscrupulous assault of the dark forces

of special-interest funded denialism. And (whilst I would be pushed to find a journalist I admire more) nothing highlighted

the irritating empathy-deficient, self-righteous prig that George Monbiot can sometimes be, than when he attacked Phil

Jones over the UAE emails affair. Its really our academic system, perhaps, that I am actually having a poke at because I

think it's the way everything is divided up into specialisms into which academics are slotted and within which they begin

to build their little empires that is at the root of my criticism. But it seems so often that whenever the climate debate

hits upon one of these specialisms there has to be some expert who crawls out from under his (or her) specialist rock to

say, no you can't say that, actually its more complicated than this, you have to listen to me on this. Well maybe

they're actually right (they must be to some degree, sometimes) and its just my cynicism that suggests they are simply

defending their academic territory and that sometimes behind the dense fog of their complexities what I would call the

'bleedin obvious' is slithering out of our grasp.

Anyway, what I can now do is point to the work of a well esteemed scientific institution, the Tyndall Centre, and of a

particular scientist, Kevin Anderson, whose stringent analysis - coming from a completely different angle to the one I am

coming from - blows most of the conventional assumptions about how much we have to reduce emissions by when, completely

out of the water. As I understand it Anderson accepts (and does not try to critique) the conventional 'consenus' science

but simply analyses the statistics upon which the models or 'pathways' for emissions reductions are constructed. He finds

the conventional statistics upon which all of our political initiatives on climate are based (from those debated at the

conferences of the UNFCCC to the UK's Climate Act) utterly flawed and unfit for purpose. In the light of his withering

analysis (and you will have to check out of one of his devastating presentations to see what I mean - see

here, or a more

recent version here ) in which the fabled

'two degree' safe limit to the increase in global temperature fades into the mists of unattainability, the whole of the

conventional climate debate is seen to be based not on the science but basically on a statistical con-trick, upon which has

been constructed a mythology which has gained credence due partly to no more than the frequency with which it is repeated.

That and the pressure from economists and politicians to make the figures suit their own theories, ideologies, and of

course, electability.

Anderson, in any case, offers an extremely grim and sobering analysis of the statistics, of the gravity of our situation

and of the scale of what we need to do to have any chance of escaping the very worst of catastrophic climate impacts. Yet

even so, I am of course throwing Anderson - and even his grim conclusions - out with all the others. I do not question his

statistical critique one bit but as he himself says even his grimmest of conclusions about what we can achieve and how much

we have to do to achieve it, rests on certain assumptions one of which is that no discontinuities (tipping points) occur.

Of course this is precisely what I have suggested is occurring.

Frankly I don't believe in any of the projections or any of the figures. Two degrees is neither achievable under any of

the currently projected or currently conceivable emissions reductions pathways and neither is it any kind of 'safe' limit,

anyway. It is as Anderson suggests a purely 'political' construct. Meanwhile Bill Mckibben urges us to 'do the math' but

I don't believe his figures either - even whilst heartily supporting the basic message he is trying to get across about the

necessity of leaving fossil fuels in the ground. I don't believe in 440 parts per million as the level of atmospheric

carbon concentration which gives a global temperature of no more than about two degrees. I don't believe that 350 parts per

million is the safe level of atmospheric carbon concentration to aim at. These last two are different, I suppose, because

here I will be contradicting myself in that there are figures in this context that I do have some belief in like four degrees

as the temperature to which 440 ppm would mean we were inexorably heading (though how fast remains the critical and

extremely difficult question) and 320 ppm as something like the safe level of CO2 concentration. But all these examples

show how such figures are so often more myth than reality, answering to political or even perceived campaigning needs

rather than to the science. Those political needs are real of course, in that it is difficult to make progress without some

kind of target to aim for and the science may simply not exist yet which tells us what really is a safe target (or by how

much we've passed it already..) or what is achievable. But it's a fatal mistake to use them as any rough mental guide to

the actual physical reality of the climate change now happening around us.

Frankly I don't believe in any of the projections or any of the figures. Two degrees is neither achievable under any of

the currently projected or currently conceivable emissions reductions pathways and neither is it any kind of 'safe' limit,

anyway. It is as Anderson suggests a purely 'political' construct. Meanwhile Bill Mckibben urges us to 'do the math' but

I don't believe his figures either - even whilst heartily supporting the basic message he is trying to get across about the

necessity of leaving fossil fuels in the ground. I don't believe in 440 parts per million as the level of atmospheric

carbon concentration which gives a global temperature of no more than about two degrees. I don't believe that 350 parts per

million is the safe level of atmospheric carbon concentration to aim at. These last two are different, I suppose, because

here I will be contradicting myself in that there are figures in this context that I do have some belief in like four degrees

as the temperature to which 440 ppm would mean we were inexorably heading (though how fast remains the critical and

extremely difficult question) and 320 ppm as something like the safe level of CO2 concentration. But all these examples

show how such figures are so often more myth than reality, answering to political or even perceived campaigning needs

rather than to the science. Those political needs are real of course, in that it is difficult to make progress without some

kind of target to aim for and the science may simply not exist yet which tells us what really is a safe target (or by how

much we've passed it already..) or what is achievable. But it's a fatal mistake to use them as any rough mental guide to

the actual physical reality of the climate change now happening around us.

Meanwhile we are left in a position whereby even the 'good guys', the progressives in the actual political debate, those

pushing for action, are basing their argument on what is more 'mythology' than scientific reality. The basic premise of

their own position, in terms of what they offer as a meaningful response to the climate threat, is deeply flawed. Of

course in trying to advance any action on climate change they are up against the blindest ignorance at best and the most

cynical of wilful distortions at worst and to some extent this has pushed them into the corner they are in. For a number

of reasons that include the sheer unprecedented magnitude of what is happening, but also skilful and deliberate distortion

of the debate by powerful vested interests motivated by short term profit, the public and political debate has become a

largely debased and spurious one, still focussed on whether climate change is 'real', or at least really serious, rather

than the precise degree and rapidity of the devastation it will bring upon us. Meanwhile the physical reality has marched

off elsewhere, leaving this public argument a very great distance behind. Of course the real argument about just how bad it

will get how quickly is being held in some scientific circles but greatly to the discredit of a media that is largely

complacent or timid - at best - this, the real argument, rarely penetrates to the public.

That anyway is my view. The reason above all I have developed an allergy to the projections and the figures that go with

those is that they suggest a degree of certainty about the future we simply do not have. Most vividly illustrated by the

possibility, or might it be likelihood, that we have to put it in what may be a somewhat simplistic, or at least

simplified, way 'hit a tipping point'. There are factors taking over that are outside almost all the models underlying

conventional, or currently accepted, projections. Along the lines I have already hinted our best chance to get any idea

what actually is in store for us, might be send an army of Peter Wadhamses up to the Arctic and tundra regions to research

and monitor in as much detail as possible what is actually happening there. Given the magnitude of what's at stake then

spending a sum equivalent to what we now spend on, say - defense - would not be inappropriate.

But what I am most keen to focus on is how this reality should be expressed in our campaigning, and in the language we

use in our campaigning. There are a whole bunch of commonly repeated assertions that are simply not true. That if we only

do the right thing there is definitely still time. That we have the technical means: the only barrier is political will.

All bets are off that even if we pull together (in what would amount to a political miracle) right now and start

energetically doing all the things we ought to do - that that will be enough to forestall catastrophe. Someone will say

that if we admit that it will be hugely disempowering. Well in the short term then in a sense, maybe. But actually in the

long term there is nothing more disempowering and soul destroying than the steady erosion of comforting illusions, the

crumbling away under one's very feet of the foundation of all our hopes and strategies for the future. The greatest mistake

that campaigners could make is the one they are largely making: that is supporting the 'mythology' I have talked about on

the grounds of immediate political expediency. Any short term political gains may not in the long run be worth giving

credibility to an illusion, the shattering of which may ultimately have a devastating psychological impact.

Most of all the whole language of 'is it too late or isn't it ?' should be abandoned. There is a danger in the 'hundred

days' type strategy, for instance, and its obvious enough: what do you do when the 'hundred days' is over: just give up ?

This was a problem with the whole Copenhagen approach. The Copenhagen Conference was our 'last chance' and there was a

kind of inescapable logic inherent in this, that given that in the event the Conference was in fact something of a

train-wreck, then, subsequently, we might as well give up. In actual fact the NGOs seem in many ways to have confirmed this

analysis by giving every appearance of actually having given up, or at least having drastically turned down the pressure,

on the climate issue post-Copenhagen but that is another question (see my previous blogs

here and

here). Now there is an

almost inevitable tendency to want to preserve the sense of hope, which had been the mainstay

of the 'There is still hope if we act at Copenhagen / in a 100 days / by 2015 / etc type of approach' which means we are

drawn to ever more shrill and more desperate exhortations to achieve x target by x deadline.... but with the increasing

shrillness and desperation (themselves entirely in order) there is an increasing lack of credibility in the meaningfulness

of the target and deadline, and therefore of the 'hope' which is based on them. And in fact what we have actually been

seeing is that its very likely that conventional estimates are overoptimistic (maybe wildly) and that these assorted targets

and deadlines have likely been pretty meaningless for some time now. This is certainly the

case if, as I have suggested, we have 'hit a tipping point'.

Most of all the whole language of 'is it too late or isn't it ?' should be abandoned. There is a danger in the 'hundred

days' type strategy, for instance, and its obvious enough: what do you do when the 'hundred days' is over: just give up ?

This was a problem with the whole Copenhagen approach. The Copenhagen Conference was our 'last chance' and there was a

kind of inescapable logic inherent in this, that given that in the event the Conference was in fact something of a

train-wreck, then, subsequently, we might as well give up. In actual fact the NGOs seem in many ways to have confirmed this

analysis by giving every appearance of actually having given up, or at least having drastically turned down the pressure,

on the climate issue post-Copenhagen but that is another question (see my previous blogs

here and

here). Now there is an

almost inevitable tendency to want to preserve the sense of hope, which had been the mainstay

of the 'There is still hope if we act at Copenhagen / in a 100 days / by 2015 / etc type of approach' which means we are

drawn to ever more shrill and more desperate exhortations to achieve x target by x deadline.... but with the increasing

shrillness and desperation (themselves entirely in order) there is an increasing lack of credibility in the meaningfulness

of the target and deadline, and therefore of the 'hope' which is based on them. And in fact what we have actually been

seeing is that its very likely that conventional estimates are overoptimistic (maybe wildly) and that these assorted targets

and deadlines have likely been pretty meaningless for some time now. This is certainly the

case if, as I have suggested, we have 'hit a tipping point'.

But what does 'too late' actually mean ? And what precisely are we tipping into ? Is this the 'end of the world' ? Well,

no, not literally certainly: there's no reason to believe the roughly spherical piece of rock that is the earth won't go

on spinning on its axis and orbiting the sun for some time yet - whatever huge blunders humanity embarks on. But does it

mean the end of human life ? Or all life ? Hansen has outlined a theoretical scenario where this would be the case

(in his book "Storms of my Grandchildren",

chapter 10). But

it is highly theoretical, to say the least, not supported by any considerable consensus and with vast areas of

uncertainty and, one would imagine, a rather larger window of opportunity to act before we hit the absolute certainty of

total doomsday in this sense. None of which means we should totally dismiss it but clearly in the face of the overwhelming

moral imperative to save life even if that be a theoretical extreme of just one or two lives out of nine billion then

we are not entitled to 'give up' on the basis of this - or any other - highly theoretical and conditional

prediction of doomsday.

But what does 'too late' actually mean ? And what precisely are we tipping into ? Is this the 'end of the world' ? Well,

no, not literally certainly: there's no reason to believe the roughly spherical piece of rock that is the earth won't go

on spinning on its axis and orbiting the sun for some time yet - whatever huge blunders humanity embarks on. But does it

mean the end of human life ? Or all life ? Hansen has outlined a theoretical scenario where this would be the case

(in his book "Storms of my Grandchildren",

chapter 10). But

it is highly theoretical, to say the least, not supported by any considerable consensus and with vast areas of

uncertainty and, one would imagine, a rather larger window of opportunity to act before we hit the absolute certainty of

total doomsday in this sense. None of which means we should totally dismiss it but clearly in the face of the overwhelming

moral imperative to save life even if that be a theoretical extreme of just one or two lives out of nine billion then

we are not entitled to 'give up' on the basis of this - or any other - highly theoretical and conditional

prediction of doomsday.

That does not mean that we should shirk hard and bitter realities, of course, like what must now be an overwhelming

probability that we have already condemned millions more probably billions to misery and death. To some extent this has

been unwitting but of course more and more it has become the result of our wilful short termism and greed (without

elaborating further on

the irresponsibility of politicians, breathtaking cynicism of special interest groups etc..etc..). Think cosy warm feeling

around the saving of tens or hundreds of thousands through 'Band Aid' and the like, invert it (into whatever is the

precise

opposite of 'cosy warm feeling') and multiply by hundreds, thousands or whatever. That, psychologically, is probably where

we should be. If you follow me. I don't wish mental anguish on anyone least of all those few actually doing anything

about this, and least of all do I endure any such condition myself but I do mean that at least just a little of this

discomfort should penetrate to the wider society at large it does not need ever more sugar-coated pretence and promises

of bogus hope.

What I am saying of course is that even if the future looks, and almost inevitably will be, bleak, there is every

probability that there is still a very great deal to 'play for'. A realistic way of looking at it might be to say that

humanity is heading for a 'bottleneck' - in terms of its onwards progress and probably numbers and that what we are

playing for is just how narrow or wide that 'bottleneck' will be. Another way of looking at it would be to use the analogy

of War, which is a horrific possibility we should do everything to avoid but once its broken out then we are surely not

wrong to concentrate on minimising the casualties (and of course there's no equivalent of the moral negative of wishing

maximum casualties on 'the other side' in this case). In a sense this is the message we should be giving out we are

already at war, things will be grim, there will surely be 'blood, sweat and tears' but there is still a great deal to play

for. What we should not be giving out is any kind of false promise that if we can only act now all will be OK, or even

that through the transition into the necessary low carbon society we shall metamorphosose effortlessly into some kind of

Green Utopia (I for one do not believe that all the intractable agonies of the human condition will ever resolve so easily).

That does not mean that there are not indeed some 'win-win' solutions and plenty of 'low hanging fruit' in terms of

relatively easy things we could start doing right now. We just should not kid ourselves or anybody else that they will be

anything like enough. Of course its true that while the crisis we face is almost immeasurably vast and terrifying its also

true that we've barely started in terms of doing anything really meaningful about it. I am prone at this point in the

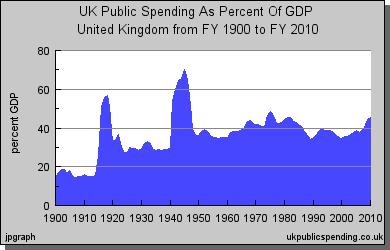

argument to return to the war analogy and note the scale of effort that has been generated in the face of 'national

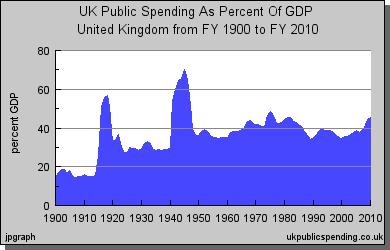

emergencies' of the past. Just look at it financially in terms of the proportion of GDP spent by government essentially

on fighting either of the past world wars. Something like 40 or 50 % - not the one per cent per annum predicated by

Stern as what we need to spend to prevent catastrophic climate change. Its true we've barely started to make any real

effort at all, so far.

That does not mean that there are not indeed some 'win-win' solutions and plenty of 'low hanging fruit' in terms of

relatively easy things we could start doing right now. We just should not kid ourselves or anybody else that they will be

anything like enough. Of course its true that while the crisis we face is almost immeasurably vast and terrifying its also

true that we've barely started in terms of doing anything really meaningful about it. I am prone at this point in the

argument to return to the war analogy and note the scale of effort that has been generated in the face of 'national

emergencies' of the past. Just look at it financially in terms of the proportion of GDP spent by government essentially

on fighting either of the past world wars. Something like 40 or 50 % - not the one per cent per annum predicated by

Stern as what we need to spend to prevent catastrophic climate change. Its true we've barely started to make any real

effort at all, so far.

And then of course I talked about the 'window of opportunity to act' before the certainty of total doomsday. This raises

the question of what kind of 'action' might be possible. In the face of absolute dire extremity who knows what human

ingenuity might come up with ? How many could predict the Atom bomb - or come to that the telephone or radio - before

they happened.? And it is of course precisely in the face of dire emergency that human ingenuity flourishes most - anyway

that's what one could argue. So here is yet more uncertainty to undermine any vaunted 'inevitability' of an ultimate

doomsday scenario (and undermine it we should since such a sense of inevitabiity and the fatalism it engenders can be as

inimical to real constructive action on climate as the denialist lie that there is no significant problem at all.)

However when we talk about 'human ingenuity in the face of dire emergency' like this it must in the current context at

least bring us stumbling into another controversy. This is the controversial topic that any discussion about the direness

of the current climate emergency will inevitably be attracted towards sooner or later and which goes, loosely at least,

under the label of 'geo-engineering'.

'Geoengineering'

is not a very well defined term that covers a 'multitude of sins'. One can say, however, that there are

two very different types of

climate-remedial techniques that often bear this label. One involves managing and trying to reduce the amount of energy in

the form of solar radiation that reaches us and thus directly effects the energy balance and so temperature, of the planet.

An example might be putting a giant mirror in space to reflect away the sun's rays but this is the most unrealistic

possibility: much more realistic methods involve putting sulphates or other dirty pollutants in the atmosphere that have

the effect simply of blocking the sun's rays in the way that a giant sun-shade would - albeit obviously only as a very

partial kind of sunshade, in this case. The second type involves taking carbon dioxide and/or other greenhouse gases out

of the atmosphere: a more indirect method of impacting the climate but a more direct way of dealing specifically with the

man-made problem of excess greenhouse gases. The latter method is far less risky than the former, but at the same time the

various methods all tend to make a rather small dent on the problem very slowly and usually very expensively, whilst many

are beset with a variety of attendant problems. There is a pretty comprehensive review in the

Friends of the Earth report

'Negatonnes'. Needless to say it is in every case infinitely easier and cheaper not to put excess greenhouse gases into the

atmosphere in the first place than to try to take them out again later. Nevertheless Friends of the Earth is now prepared

to support, in a very qualified kind of way, the further development and use of these 'negatonnes' techniques.

'Geoengineering'

is not a very well defined term that covers a 'multitude of sins'. One can say, however, that there are

two very different types of

climate-remedial techniques that often bear this label. One involves managing and trying to reduce the amount of energy in

the form of solar radiation that reaches us and thus directly effects the energy balance and so temperature, of the planet.

An example might be putting a giant mirror in space to reflect away the sun's rays but this is the most unrealistic

possibility: much more realistic methods involve putting sulphates or other dirty pollutants in the atmosphere that have

the effect simply of blocking the sun's rays in the way that a giant sun-shade would - albeit obviously only as a very

partial kind of sunshade, in this case. The second type involves taking carbon dioxide and/or other greenhouse gases out

of the atmosphere: a more indirect method of impacting the climate but a more direct way of dealing specifically with the

man-made problem of excess greenhouse gases. The latter method is far less risky than the former, but at the same time the

various methods all tend to make a rather small dent on the problem very slowly and usually very expensively, whilst many

are beset with a variety of attendant problems. There is a pretty comprehensive review in the

Friends of the Earth report

'Negatonnes'. Needless to say it is in every case infinitely easier and cheaper not to put excess greenhouse gases into the

atmosphere in the first place than to try to take them out again later. Nevertheless Friends of the Earth is now prepared

to support, in a very qualified kind of way, the further development and use of these 'negatonnes' techniques.

The problem is that this is really ducking the central dilemma because if we have indeed 'hit a tipping point', if, for

instance, as the 'Arctic Methane Emergency Group' claim we have only a few years to act

before the whole situation around

the Arctic feedbacks spins out of control, then we would need to do something that might have a rather big impact very fast.

Now the solar radiation techniques might do this but are extremely risky and hard to control. The reason why FOE is prepared

to support, to a limited degree, the other kind of techniques is precisely because they are much less risky and are indeed

easier to control. They address only the specific problem we have of excess greenhouse gases without threatening to change

the whole planetary climate in ways that we might not be able to predict or control.

Furthermore they have been more or less forced to enrol the 'negatonne' type techniques to keep alive the rapidly

evaporating sense of 'hope' that they attach to their latest, and most desperate attempt to hypothesise a target/deadline

that seems to preserve some credibility in terms of the latest science as being consistent with the avoidance of

catastrophic climate change (wisely no-one is talking about avoiding 'dangerous' climate change any more) whilst also being

attainable. Now I have expressed above a complete distrust of all these concoctions of figures and whilst FOE - aligning

itself with the Tyndall Centre to a great extent - is of course more rigorous in its approach than others (especially

governments) if we have indeed 'hit a tipping point' in the sense I have outlined above then all their calculations are

meaningless - even allowing for any extra leeway which 'negatonnes' give them. Of course there is in any case the

difficulty that they provide a blueprint for what looks to be firmly in the region of the politically unattainable right

now - whilst FOE have not attempted to change this, by mounting any kind of meaningful political campaign to achieve targets

anywhere near what their briefings now suggest is necessary.

So the 'negatonne' approach, taking carbon out of the atmosphere, is relatively safe and controllable but does far too

little too slowly. By contrast the most obvious means of reducing the solar radiation that is absorbed by the earth is in

a sense a technique already proven to work on a pretty large scale. Its what happens every time there is a major volcano,

with recorded significant, though temporary, cooling impacts on global climate from major eruptions - and is what is

reasonably predicted to be what would happen in the event of any kind of 'nuclear winter'.

We are talking in both cases

about the the solar radiation blocking, 'sun-shade' effect of the substances thrown into the atmosphere by these events,

especially sulphate emissions. Moreover this is actually something human beings have actually been doing - though

inadvertantly - in a slow steady kind of way for some time. The current global average temperature is the outcome of a

balance between anthropogenic warming and

cooling. The 'cooling' (hard to quantify but see now

here) is precisely caused by the solar radiation blocking, 'sun-shade' (or 'global

dimming') effect of the sulphate emissions associated with dirty industry - today mostly in Southern and Eastern Asia (see

further here with update

here and in great detail

here). If

we stopped all kinds of pollution (CO2 and sulphates and everything else) today then we would see a rapid, if temporary,

rise (a 'spike') in temperatures because whereas the cooling sulphates would rapidly fall out of the atmosphere (if not

sustained by constant emissions) the heat-trapping CO2 would stay there (for a very considerable time). However if we are

talking about doing something deliberate (like targeted release of sulphates into the stratosphere through some kind of

giant 'chimney') on a scale sufficient to have any impact on global or regional (Arctic) temperatures then we would indeed

be playing with fire because once released we would have no control over the massive sulphate emissions that would be

required, and the possible negative side effects on the complex global climate systems are probably incalculable. Already

the sulphate emissions associated with dirty European industry before it was cleaned up have been

very plausibly

associated with the droughts that produced the Ethiopian famine of 'Band Aid' fame. So the potential for negative side

effects is huge, not to say for simply making a bad situation even worse. It is true there are variations on this theme

like trying to create clouds that would reflect away solar radiation instead

for instance by spraying sea water into the

atmosphere in some clever controlled way - but these are quite unproven whilst anything attempted on a scale necessary for

meaningful remedial impact would very likely have a concomitant potential for an equivalent scale of unintended negative

impact, one way or another.

We are talking in both cases

about the the solar radiation blocking, 'sun-shade' effect of the substances thrown into the atmosphere by these events,

especially sulphate emissions. Moreover this is actually something human beings have actually been doing - though

inadvertantly - in a slow steady kind of way for some time. The current global average temperature is the outcome of a

balance between anthropogenic warming and

cooling. The 'cooling' (hard to quantify but see now

here) is precisely caused by the solar radiation blocking, 'sun-shade' (or 'global

dimming') effect of the sulphate emissions associated with dirty industry - today mostly in Southern and Eastern Asia (see

further here with update

here and in great detail

here). If

we stopped all kinds of pollution (CO2 and sulphates and everything else) today then we would see a rapid, if temporary,

rise (a 'spike') in temperatures because whereas the cooling sulphates would rapidly fall out of the atmosphere (if not

sustained by constant emissions) the heat-trapping CO2 would stay there (for a very considerable time). However if we are

talking about doing something deliberate (like targeted release of sulphates into the stratosphere through some kind of

giant 'chimney') on a scale sufficient to have any impact on global or regional (Arctic) temperatures then we would indeed

be playing with fire because once released we would have no control over the massive sulphate emissions that would be

required, and the possible negative side effects on the complex global climate systems are probably incalculable. Already

the sulphate emissions associated with dirty European industry before it was cleaned up have been

very plausibly

associated with the droughts that produced the Ethiopian famine of 'Band Aid' fame. So the potential for negative side

effects is huge, not to say for simply making a bad situation even worse. It is true there are variations on this theme

like trying to create clouds that would reflect away solar radiation instead

for instance by spraying sea water into the

atmosphere in some clever controlled way - but these are quite unproven whilst anything attempted on a scale necessary for

meaningful remedial impact would very likely have a concomitant potential for an equivalent scale of unintended negative

impact, one way or another.

There are some other very negative aspects of this type of geo-engineering it is necessary to list. First is the 'moral

hazard' problem. We know for a certainty, given the politics already seen to be at play around climate change that

geoengineering of this kind would be used as an excuse for not reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. Second there is the

likelihood that the industries involved in actually carrying it out would have a malign influence on the political

decision making that would be needed to initiate and control it. In other words it would be done in the interests of those

companies' profits rather than in the best interests of the planet. A perfect example of this kind of thing is provided by

'biofuels': originally a perfectly genuine proposed solution but one which has proved to have had a far more negative

impact than a positive one - in terms mainly of its impact on food prices and deforestation - which has continued far too

unchecked and uncontrolled due to the malign influence of the commercial bandwagon that has built up around it. There is

the potential for an unspeakable nightmare here in terms of the profit motivated misuse of geoengineering technologies with

the potential to destroy life on a massive scale - and this is not to mention the potential for international conflict over

how geoengineering is used, controlled by whom, in whose interests, with how much 'collateral damage' suffered by whom

etc..etc...

However none of this, however true, is an argument to suggest that we could not reach a situation, or already have reached

a situation, where the outcome without intervention would be so catastrophic that some kind of geoengineering was

essentially 'our only chance'. We could be in a situation where we could not - morally - rule out

geoengineering if it offered just the slenderest hope against an overwhelming probability of really massive unspeakable

catastrophe from 'runaway' climate change. In other words the dilemma, or at least potential dilemma, is entirely real

and not something we can quickly

resolve or escape. Completely ruling out large scale geoengineering (Friends of the Earth's position as I understand it)

could only really be justified if we had more certainty about the seriousness of the current situation than we are actually

able to have. It is not something that can be lightly removed from the table, altogether.

On the other hand this article is not going to try and resolve the dilemma either. Instead we will try and draw whatever

conclusions we can that will be true in any case, whether or not large scale geoengineering is, or ever becomes,

justifiable. The obvious conclusion we can certainly draw is the boringly familiar one that we need to reduce emissions of

greenhouse gases as rapidly as we can. Whilst all the figures and 'deadlines' associated with projected pathways to avoid

catastrophe may be unreal the sense of urgency that they invoke is completely justified and real: there can

be little doubt that in general terms the scale of potential catastrophe increases and our options for dealing with it

diminish exponentially with every year, week, or day's delay in reducing our emissions of greenhouse gases. It is virtually

inconceivable that any kind of geoengineering could work, in the long term, without also reducing emissions - imagine for

instance the scenario of injecting ever more and more sulphates into the atmosphere ad infinitum - and also given the

enormous hazards associated with geoengineering outlined above it is pretty clear that the less of it we have to do

(preferably none at all) then the better. In general terms, the more and quicker we reduce emissions the less we will

need to resort to any kind of geoengineering. And again we may well need to find some ways of actually taking greenhouse

gases out of the atmosphere but it would be madness to be doing this whilst also continuing to spew out yet more greenhouse

gases into it. In the end we - the global community - will need to be in a position where we are in control of the

composition of our atmosphere and the easiest way to do this, or at least the necessary first step, will always be to be in

control of what we put into it.

To say simply that we need to reduce emissions as rapidly as possible is indeed a boringly familiar conclusion that might

come as an anti-climax to an article that has been prepared to upset orthodoxies. But the point is of course precisely that

the boringly orthodox overarching goal of climate campaigning remains true - and it might in particular merit restating as

the shadow of the necessity for additional geoengineering-type techno-fixes grows longer. There is nothing wrong

with techno-fixes per se to the extent that they they work - and don't have (disproportionately large) damaging side

effects. This is true of geoengineering and, say, nuclear power (without making a judgement as to what works best or where

limited resources should be expended). But what surely is damaging is the illusion that techno-fixes are the whole

answer,

that it can all be left to the scientists and technicians without the rest of us having to make any effort and without the

need to fight any kind of political battle to ensure that difficult and very probably unpopular decisions are taken. The

worst part of the techno-fix approach is the kind of fatalistic acceptance that political battles are too hard to win

but

can be circumvented by technologies that will make everything palatable to the masses, perhaps without the need for even

the political courage necessary to make them aware of how dire the situation we are all in really is. This is at least as

delusional as the idea that new technologies will play no role at all. Its worth referring back to Kevin Anderson's

approach at this point and reminding ourselves how often he makes the point that in terms of reducing emissions with

maximum rapidity the most feasible approach is so often simply to give things up

or at least for the rich minority who

account for the overwhelming majority of global emissions to give something up. And when he talks about how to reach some

desperately difficult emissions reductions target its that phrase 'its hard to see how anything other than a planned

recession...' that sticks in the memory.

Many have noted the likelihood that there will be, or is already building, a considerable commercial bandwagon behind

the various techno-fix approaches to climate change. That may be one reason we don't need to campaign too hard for them.

What we do need to campaign for is the harder, very likely unpopular and politically difficult things that we need to do.

This will involve a political struggle both to summon the will to do the things likely to require some real effort and

sacrifice from all of us (or at least all of us in the rich high-consuming world) and indeed to make as sure as we can that

the controlling force over policy in general and any use of techno-fixes in particular is guided by a genuine sense of

the common good rather than powerful corporate interests. We will need to project the need for something akin to a war

effort with the language appropriate to that, language which does not flinch from telling the whole truth, however grim or

shrink from calling for the great effort that will need to be made by everyone. We need to avoid promoting comforting

illusions, spurious mythologies of hope or false orthodoxies. If we are indeed, as I stated at the outset, now on a

collision course with catastrophe - albeit of unknown precise scale and degree of 'totality' - then at some stage we will

all have to face up to the full bitter truth of that and its best that we start now. Campaigners would do well to do whatever

they can to make that happen.

Previous Blogposts:

Don't mention climate change.

Funny weather we're having .... how the melting arctic is affecting global weather

patterns in a sinister way

Fracking - why we need a permanent ban.

Catching up and getting real with the climate crisis

What happened to the Arctic last year ? Well at its lowest summer extent the sea ice cover shrunk back around 700,000 sq

km more than it ever has before - to an area roughly half the average from 1979 to 2000. Meanwhile the situation as to the

volume of ice is a little more controversial due to the greater difficulty of measurement but it is certainly a lot more

dramatic with maybe 70 to 80 % disappeared, and diminishing on a trajectory, which, according to Professor Peter Wadhams

from the Cambridge University Polar Ocean Physics Group will bring us to essentially zero end of summer sea ice by 2015

(see

further here and here ).

What happened to the Arctic last year ? Well at its lowest summer extent the sea ice cover shrunk back around 700,000 sq

km more than it ever has before - to an area roughly half the average from 1979 to 2000. Meanwhile the situation as to the

volume of ice is a little more controversial due to the greater difficulty of measurement but it is certainly a lot more

dramatic with maybe 70 to 80 % disappeared, and diminishing on a trajectory, which, according to Professor Peter Wadhams

from the Cambridge University Polar Ocean Physics Group will bring us to essentially zero end of summer sea ice by 2015

(see

further here and here ).

Given that Professor Wadham's credibility has received a huge boost from the dramatically precipitate crash in sea ice last

year we would be very unwise to dismiss his prediction, based as he says on a measured trend. What that means is that

what was - a decade or so ago - routinely predicted not to happen till the end of the century, or maybe 80 years hence, is

happening, essentially, right now. There could hardly be a more dramatic, nor a more clear cut, demonstration of the fact

that climate change is happening far quicker than anyone predicted and that the predictions of the scientists are falling

way short of the reality: even the scientists have been left floundering in the wake of the climate change behomoth, forever

struggling to revise upwards their estimates of its scale and speed. With a few exceptions this has been overwhelmingly

the case across the board (just compare standard scientific estimates from 10, from 20, years ago in so many fields) but

the precipitate decline of arctic sea ice is the clearest and most dramatic.

Given that Professor Wadham's credibility has received a huge boost from the dramatically precipitate crash in sea ice last

year we would be very unwise to dismiss his prediction, based as he says on a measured trend. What that means is that

what was - a decade or so ago - routinely predicted not to happen till the end of the century, or maybe 80 years hence, is

happening, essentially, right now. There could hardly be a more dramatic, nor a more clear cut, demonstration of the fact

that climate change is happening far quicker than anyone predicted and that the predictions of the scientists are falling

way short of the reality: even the scientists have been left floundering in the wake of the climate change behomoth, forever

struggling to revise upwards their estimates of its scale and speed. With a few exceptions this has been overwhelmingly

the case across the board (just compare standard scientific estimates from 10, from 20, years ago in so many fields) but

the precipitate decline of arctic sea ice is the clearest and most dramatic.  One should note that the Arctic has been warming disproportionately faster than the rest of

the planet (in part because of feedbacks already in operation) and that is part of the reason for why we are where we are

but the relevant feedbacks now set to dramatically accelerate the warming process include diminished albedo (that is

reflection away of the sun's heat) from diminished sea ice and seasonal snow cover on land (with dark ocean or land surfaces

absorbing more heat), release of carbon, mainly in the form of methane, from melting permafrost on land and release of

yet more methane from the methane hydrates under the sea. Professor Wadhams

One should note that the Arctic has been warming disproportionately faster than the rest of

the planet (in part because of feedbacks already in operation) and that is part of the reason for why we are where we are

but the relevant feedbacks now set to dramatically accelerate the warming process include diminished albedo (that is

reflection away of the sun's heat) from diminished sea ice and seasonal snow cover on land (with dark ocean or land surfaces

absorbing more heat), release of carbon, mainly in the form of methane, from melting permafrost on land and release of

yet more methane from the methane hydrates under the sea. Professor Wadhams

There is, meanwhile,

maybe twice as much carbon in the permafrost than currently in the atmosphere whilst an even greater quantity resides in

the methane hydrates, massive releases from which have been implicated as the dominant mechanism behind several of the

extinction events from the distant geological past, in particular the

There is, meanwhile,

maybe twice as much carbon in the permafrost than currently in the atmosphere whilst an even greater quantity resides in

the methane hydrates, massive releases from which have been implicated as the dominant mechanism behind several of the

extinction events from the distant geological past, in particular the

Before tackling the likely longer term implications of that we can take a look at how this is actually affecting us,

already, right now. Recent studies have increasingly suggested that not only are extreme weather events increasing in line

with increased global temperature and energy in the system (demonstrated statistically in a

Before tackling the likely longer term implications of that we can take a look at how this is actually affecting us,

already, right now. Recent studies have increasingly suggested that not only are extreme weather events increasing in line

with increased global temperature and energy in the system (demonstrated statistically in a

Frankly I don't believe in any of the projections or any of the figures. Two degrees is neither achievable under any of

the currently projected or currently conceivable emissions reductions pathways and neither is it any kind of 'safe' limit,

anyway. It is as Anderson suggests a purely 'political' construct. Meanwhile Bill Mckibben urges us to 'do the math' but

I don't believe his figures either - even whilst heartily supporting the basic message he is trying to get across about the

necessity of leaving fossil fuels in the ground. I don't believe in 440 parts per million as the level of atmospheric

carbon concentration which gives a global temperature of no more than about two degrees. I don't believe that 350 parts per

million is the safe level of atmospheric carbon concentration to aim at. These last two are different, I suppose, because

here I will be contradicting myself in that there are figures in this context that I do have some belief in like four degrees

as the temperature to which 440 ppm would mean we were inexorably heading (though how fast remains the critical and

extremely difficult question) and 320 ppm as something like the safe level of CO2 concentration. But all these examples

show how such figures are so often more myth than reality, answering to political or even perceived campaigning needs

rather than to the science. Those political needs are real of course, in that it is difficult to make progress without some

kind of target to aim for and the science may simply not exist yet which tells us what really is a safe target (or by how

much we've passed it already..) or what is achievable. But it's a fatal mistake to use them as any rough mental guide to

the actual physical reality of the climate change now happening around us.

Frankly I don't believe in any of the projections or any of the figures. Two degrees is neither achievable under any of

the currently projected or currently conceivable emissions reductions pathways and neither is it any kind of 'safe' limit,

anyway. It is as Anderson suggests a purely 'political' construct. Meanwhile Bill Mckibben urges us to 'do the math' but

I don't believe his figures either - even whilst heartily supporting the basic message he is trying to get across about the

necessity of leaving fossil fuels in the ground. I don't believe in 440 parts per million as the level of atmospheric

carbon concentration which gives a global temperature of no more than about two degrees. I don't believe that 350 parts per

million is the safe level of atmospheric carbon concentration to aim at. These last two are different, I suppose, because

here I will be contradicting myself in that there are figures in this context that I do have some belief in like four degrees

as the temperature to which 440 ppm would mean we were inexorably heading (though how fast remains the critical and

extremely difficult question) and 320 ppm as something like the safe level of CO2 concentration. But all these examples

show how such figures are so often more myth than reality, answering to political or even perceived campaigning needs

rather than to the science. Those political needs are real of course, in that it is difficult to make progress without some

kind of target to aim for and the science may simply not exist yet which tells us what really is a safe target (or by how

much we've passed it already..) or what is achievable. But it's a fatal mistake to use them as any rough mental guide to

the actual physical reality of the climate change now happening around us. Most of all the whole language of 'is it too late or isn't it ?' should be abandoned. There is a danger in the 'hundred

days' type strategy, for instance, and its obvious enough: what do you do when the 'hundred days' is over: just give up ?

This was a problem with the whole Copenhagen approach. The Copenhagen Conference was our 'last chance' and there was a

kind of inescapable logic inherent in this, that given that in the event the Conference was in fact something of a

train-wreck, then, subsequently, we might as well give up. In actual fact the NGOs seem in many ways to have confirmed this

analysis by giving every appearance of actually having given up, or at least having drastically turned down the pressure,

on the climate issue post-Copenhagen but that is another question (see my previous blogs

Most of all the whole language of 'is it too late or isn't it ?' should be abandoned. There is a danger in the 'hundred

days' type strategy, for instance, and its obvious enough: what do you do when the 'hundred days' is over: just give up ?

This was a problem with the whole Copenhagen approach. The Copenhagen Conference was our 'last chance' and there was a

kind of inescapable logic inherent in this, that given that in the event the Conference was in fact something of a

train-wreck, then, subsequently, we might as well give up. In actual fact the NGOs seem in many ways to have confirmed this

analysis by giving every appearance of actually having given up, or at least having drastically turned down the pressure,

on the climate issue post-Copenhagen but that is another question (see my previous blogs

But what does 'too late' actually mean ? And what precisely are we tipping into ? Is this the 'end of the world' ? Well,

no, not literally certainly: there's no reason to believe the roughly spherical piece of rock that is the earth won't go

on spinning on its axis and orbiting the sun for some time yet - whatever huge blunders humanity embarks on. But does it

mean the end of human life ? Or all life ? Hansen has outlined a theoretical scenario where this would be the case

(in his book

But what does 'too late' actually mean ? And what precisely are we tipping into ? Is this the 'end of the world' ? Well,

no, not literally certainly: there's no reason to believe the roughly spherical piece of rock that is the earth won't go

on spinning on its axis and orbiting the sun for some time yet - whatever huge blunders humanity embarks on. But does it

mean the end of human life ? Or all life ? Hansen has outlined a theoretical scenario where this would be the case

(in his book  That does not mean that there are not indeed some 'win-win' solutions and plenty of 'low hanging fruit' in terms of

relatively easy things we could start doing right now. We just should not kid ourselves or anybody else that they will be

anything like enough. Of course its true that while the crisis we face is almost immeasurably vast and terrifying its also

true that we've barely started in terms of doing anything really meaningful about it. I am prone at this point in the

argument to return to the war analogy and note the scale of effort that has been generated in the face of 'national

emergencies' of the past. Just look at it financially in terms of the proportion of GDP spent by government essentially

on fighting either of the past world wars. Something like 40 or 50 % - not the one per cent per annum predicated by

Stern as what we need to spend to prevent catastrophic climate change. Its true we've barely started to make any real

effort at all, so far.

That does not mean that there are not indeed some 'win-win' solutions and plenty of 'low hanging fruit' in terms of

relatively easy things we could start doing right now. We just should not kid ourselves or anybody else that they will be

anything like enough. Of course its true that while the crisis we face is almost immeasurably vast and terrifying its also

true that we've barely started in terms of doing anything really meaningful about it. I am prone at this point in the

argument to return to the war analogy and note the scale of effort that has been generated in the face of 'national

emergencies' of the past. Just look at it financially in terms of the proportion of GDP spent by government essentially

on fighting either of the past world wars. Something like 40 or 50 % - not the one per cent per annum predicated by

Stern as what we need to spend to prevent catastrophic climate change. Its true we've barely started to make any real

effort at all, so far.

We are talking in both cases

about the the solar radiation blocking, 'sun-shade' effect of the substances thrown into the atmosphere by these events,

especially sulphate emissions. Moreover this is actually something human beings have actually been doing - though

inadvertantly - in a slow steady kind of way for some time. The current global average temperature is the outcome of a

balance between anthropogenic warming and

cooling. The 'cooling' (hard to quantify but see now

We are talking in both cases

about the the solar radiation blocking, 'sun-shade' effect of the substances thrown into the atmosphere by these events,

especially sulphate emissions. Moreover this is actually something human beings have actually been doing - though

inadvertantly - in a slow steady kind of way for some time. The current global average temperature is the outcome of a

balance between anthropogenic warming and

cooling. The 'cooling' (hard to quantify but see now